Welcome aboard The Bus!

The Stop

For about 50 years, from 1570 - 1620, the revenge tragedy was a favourite form of Elizabethan and Jacobean drama.1 A play in which the ‘dominant motive is revenge for a real or imagined injury,’ this theme - and its fatal consequences - is intricately detailed through the elaborate unfolding of the protagonist's revenge plot. Championing private rather than public (i.e., state-sanctioned or judicial) revenge, there is contention as to whether those protagonists seeking revenge are heroes or villains - is a character seeking revenge for the murder of his son in the right or wrong? However, this is rarely addressed in the plays themselves as their plots inevitably lead not only to the death of those on whom revenge was sought, but frequently the avenger, too.2

Beginning with the Ancient Greeks and finding its first formal expression in the plays of the Roman philosopher and playwright Seneca,3 the pursuit of revenge quickly became a central theme in many tragedies. However, the revenge tragedy as a genre was established on the Elizabethan stage with the publication of Thomas Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy (1587). In this play, the protagonist Hieronimo discovers his son’s body which leads him into a fit of madness. After discovering the identity of his son's murderers and realising their status puts them above the law, he exacts his revenge through the staging of an intricate play-within-a-play, after which he kills himself. Hieronimo's determination to attain justice despite the weakness of the state gripped the popular imagination and a raft of similar plays quickly emerged.

There are numerous notable revenge tragedies from this period, including Shakespeare’s remarkably bloody Titus Andronicus (ca.1589-1592)4, Thomas Middleton’s The Revenger’s Tragedy (1606) and John Ford’s ‘Tis Pity She’s A Whore (1626), to name a few. The genre, however, found its ‘highest expression’ in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, though the depth of the play’s philosophical considerations and the complication of its principle characters for many scholars sets it apart. Nevertheless, it is a part of the tradition, for - like all revenge tragedies - its plot ticks off all ten of the genre’s basic conventions:

The protagonist is typically a noble character driven to deceit and cunning to avenge a terrible wrong done to him or someone else.

Noble characters often behave in ways inappropriate for their social station and can mix with characters from the lower orders.

Comedy intertwines with tragedy, not only in certain characters and dialogue, but at moments of high seriousness when the plays seem to teeter on the edge of black comedy.

The play dramatises a moral code in which personal vengeance rules and a consequent cycle of violent reprisal continues until all the principals have been slaughtered.

The setting is usually outside of England.

There is often a play within a play which conceals or reveals a murderous plot.

The plotting is complex, with a lot of intrigue.

There is frequently a ghost, often of a murdered person, calling for revenge.

Madness - both real and feigned - is present.

The tone is one of sensationalism and excitement, including physical horror, such as torture or poisoning.

Though the genre itself died out over time,5 its influence was a constant throughout the next centuries of drama and remains current today. Ask yourself - have you recently seen a play, read a book, watched a film or binged a television series in which revenge of some sort is at the heart of or is a considerable part of the storyline? It certainly might not tick all the classic boxes, but there’s a reason they were popular then - and a reason revenge remains popular today. And I’d hazard a guess that it’s not going away anytime soon.

The Detour

Today’s Detour is to ‘Raising Silver,’ a short (6:15) documentary from the ‘How Was It Made’ series produced by London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. Contemporary silversmith Ndidi Ekubia leads a tour of her inspirations and her studio, showing how she raises, chases and embosses her artworks. Inspirational and beautiful, this is a fascinating insight into an artist and her work. Definitely worth the time.

The Recommendation

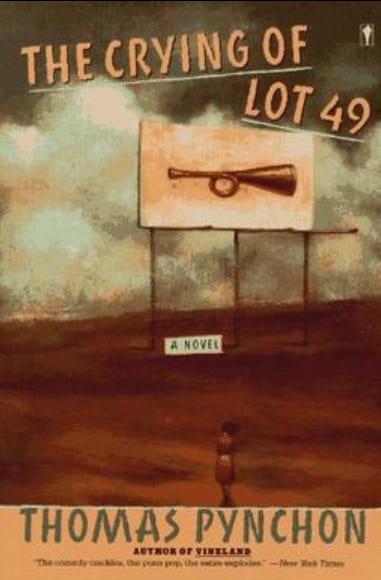

Today’s Recommendation is Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 (1966). It’s the bizarre - and very funny - story of Oedipa Maas, a disappointed California housewife who, upon receipt of news of her ex-lover's death becomes co-executor (‘or she supposed executrix’) of his estate. As Oedipa goes about settling his affairs, she stumbles across clues that suggest the existence of a secretive postal system called Tristero that potentially operates as a shadow network ‘beyond’ the established postal service. Obsessed with unravelling this mystery, she embarks on a surreal and increasingly paranoid journey across Southern California, encountering a cast of strange characters who may or may not be part of Tristero.

It’s a great novel, and one of my favourites by Pynchon, but I include it today because one of the things Oedipa uncovers along her journey is a little known (fictitious) Jacobean revenge tragedy in which this mysterious postal service plays an important part. Written by the ‘depraved’ 17th century playwright Richard Wharfinger (also fictitious), The Courier’s Tragedy is delightfully over the top and a great send up of the entire genre, not least because it functions as a play within the frame of the novel. Highly recommended.

From the back: When V was published in 1963, it was proclaimed as a new kind of novel, recalling Joyce, Beckett and Joseph Heller. Suffused with rich satire, chaotic brilliance, verbal turbulence and wild humour, The Crying of Lot 49 opens as Oedipa Maas discovers that she has been made executrix of a former lover’s estate. The performance of her duties sets her on a strange trail of detection, in which bizarre characters crowd into help or confuse her. But gradually death, drugs, madness and marriage combine to leave Oedipa in isolation on the threshold of revelation, awaiting The Crying of Lot 49.

The Sounds

Today’s playlist is a selection of five great tracks, all with a theme based one way or another on revenge: ‘One Way or Another’ (Blondie, 1978), ‘Run for Your Life’ (The Beatles, 1965), ‘These Boots are Made for Walkin’’ (Nancy Sinatra, 1966), ‘Your Time is Gonna Come’ (Led Zeppelin, 1969) and ‘I Feel So Good’ (Richard Thompson, 1991). Enjoy!

The Thought

Today’s Thought is from Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice (III.i.63), in which Shylock is pointing out the equal humanity - both good and bad - in both Christians and Jews:

‘If you prick us do we not bleed? If you tickle us do we not laugh? If you poison us do we not die? And if you wrong us shall we not revenge?’

If you have a thought on this Thought - or any part of today’s issue - please leave a comment below:

And that’s the end of this Stop - I hope you enjoyed the diversion!

Thanks to everyone who subscribes - your interest and support is truly appreciated. If you like The Bus, please SHARE it with a friend or two.

If you haven’t climbed aboard The Bus, please do!

If you like The Bus, why not check out other newsletters?

The Sample sends out articles from blogs and newsletters across the web that match your interests. If you like one, you can subscribe with one click.

Until the next Stop …

FYI: ‘Elizabethan’ refers to the period of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558-1603); ‘Jacobean’ refers to the period of the reign of King James I (1603-1625).

I love a revenge tragedy, and the more complicated and bloody the better. One of my favourite parts of teaching Hamlet has been looking at the influence of the genre on Shakespeare - which inevitably requires a quick dive into his contemporaries. Thus, the genesis of today’s Stop - sources for which include: Revenge Tragedy (Britannica), Revenge Tragedy (Wikipedia) and Studying Hamlet, EMC, London: 2017.

Seneca’s revenge tragedies include his versions of Medea, Oedipus, Agamemnon and Thyestes, to name a few. For more information, see: Seneca (Britannica).

It doesn’t get much bloodier than Titus Andronicus at this time. A quick summary (in all, there are 14 killed in the play): ‘The Roman general Titus Andronicus returns from war with four prisoners who vow to take revenge against him. They rape and mutilate Titus' daughter and have his sons killed and banished. Titus kills two of them and cooks them into a pie, which he serves to their mother before killing her too. The Roman emperor kills Titus, and Titus' last remaining son kills the emperor and takes his place.’ For more on Titus, see: Titus Andronicus (Shakespeare Birthplace Trust).

Though revenge drama films do appear. For example, Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover (1989) is a classic revenge tragedy, and - in my opinion - one of the best films of the past 50 years.

Particularly enjoyed this one, Bryan. Brought be back to the autumn of 1990, when I was in Cynthia Lewis's seminar on Elizabethan Revenge Tragedy. All of the plays you've mentioned were on the syllabus. One of my papers for that thesis focused on how to stage The Revenger's Tragedy as a comedy. Great fun.

Made me wonder if I myself have ever written one of those, and indeed, the entire trilogy 'Queen of Hearts' - appearing this year - ticks many of the boxes. Guinevere both avenges her contemporary existence and takes revenge upon those past. It is 'auto-revenge' tragedy in this sense. Her loyal companions take revenge upon arguably the two most tired tropaic scenes in Western Literature, Camelot and Calvary, by going back in time and radically rewriting them. Her younger sister takes revenge against Gwen's lover's abusive mother, and their own somewhat abusive mother then takes revenge upon herself by recklessly placing herself in the line of fire, thus getting herself killed. On and on. The nested transhistorical vengeance certainly gives the reader the distinct impression the heroines are hardly always noble, but I have waylaid at least the too-Shakespearean sensibility surrounding that motif by resetting the Arthurian characters back to their (proper) pre-Christian selves, given it was 60 years between Camlann and the first mission into England.

Good for you for also noting surely the most lurid of Beatles' songs, still to me a scandal today. But I guess in 1965 threatening revenge 'porn' against women was no big deal. Shame on the pre-Yoko Lennon. 'Man I was mean, but I'm changing my scene...' - may we all say as much.