Welcome aboard The Bus!

ARCHIVE EDITION - FIRST PUBLISHED (1.31) 21 JULY 2022

The Stop

Originally obtained from cinchona bark, quinine is used to treat malaria – an infection caused by the parasite Plasmodium falciparum, transmitted to humans by the bite of various species of (female)1 mosquitoes. For over 300 years between its introduction to Western medicine and World War I, quinine was the only effective malarial remedy. Quinine is also an ingredient in tonic water – the component that gives the drink its bitter taste – and is thus an integral part of the modern gin and tonic cocktail.2

As a component of the bark of the cinchona (quina-quina) tree, quinine was used to treat malaria at least as early as the 1600s, when it was referred to as ‘Jesuits’ bark,’ ‘cardinal’s bark,’ or ‘sacred bark’ – names stemming from its use by 17th century Jesuit missionaries in South America. Despite its connection to Catholic missionaries, there are two legends about the discovery of quinine as an anti-malarial. According to one, an Indian with a high fever drank from a pool of bitter water while lost in an Andean jungle. Realising the water had been contaminated by the surrounding quina-quina trees, when his fever left he shared his discovery with fellow villagers – who started to use the bark to treat fevers. The other legend (preferred in Europe, but debunked in 1941) told how the Spanish Countess of Chinchon - on a visit to Peru - caught a fever that was cured by the bark of a tree. She was so impressed that she introduced the bark – and thus quinine – to Spain upon her return in 1638 and in 1742 the botanist Carl Linnaeus named the tree "Cinchona" in her honour.

Regardless of its actual origin, the discovery of quinine’s anti-malarial properties was one of the greatest medical breakthroughs in the 17th century and its use as a treatment was the ‘first successful use of a chemical compound to treat an infectious disease.’ Before quinine was extracted from the cinchona bark in 1820, the bark had to be dried, ground into a fine powder and then mixed into a liquid (usually wine) before being consumed. Once it had been extracted, purified quinine replaced the bark as the standard treatment for malaria and remained the mainstay until the 1920s, when more effective synthetic anti-malarial drugs became available. However, resistance of the Plasmodium falciparum parasite to these drugs over time meant that quinine once again was brought out to play a key role in the treatment of the disease – a role it continues to play in the management of malaria today.3

The Detour

Today’s Detour is to an article from Eater, in which the author explains how it’s possible to feed yourself (well) in a rural Alaskan community. It certainly gives an insight into just how widespread Amazon Prime is ….

In Remote Alaska, Meal Planning is Everything

The Recommendation

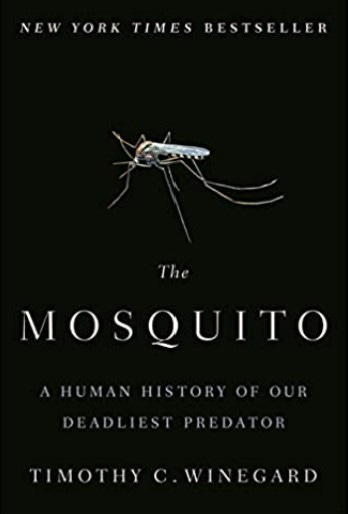

Today’s book is Timothy C. Winegard’s4 The Mosquito: A Human History of Our Deadliest Predator. I first saw this in a bookshop in Victoria, BC – and picked it up the moment I got home.5 It’s the story of the impact of this very annoying – and remarkably deadly – insect throughout human history. Spanning from the mosquito’s role in the extinction of the dinosaurs through its impact on ancient Rome, the Mongol Empire and the slave trade to its current influence around the world, the book blends storytelling, facts and science to offer another understanding of human history and our intimate connection to our world and its non-human inhabitants. A very interesting read.

From the back: ‘Across our planet since the dawn of humankind, this nefarious pest, roughly the size and weight of a grape seed, has been at the frontlines of history as the grim reaper, the harvester of human populations, and the ultimate agent of historical change. As the mosquito transformed the landscapes of civilization, humans were unwittingly required to respond to its piercing impact and universal projection of power. The mosquito has determined the fates of empires and nations, razed and crippled economies, and decided the outcome of pivotal wars, killing nearly half of humanity along the way. She (only females bite) has dispatched an estimated 52 billion people from a total of 108 billion throughout our relatively brief existence. As the greatest purveyor of extermination we have ever known, she has played a greater role in shaping our human story than any other living thing with which we share our global village.’

Here is a review from NPR: The Mosquito

The Sounds

Today’s playlist is composed of five songs about mosquitos and gin: ‘Mosquito Song’ (Queens of the Stone Age, 2002), ‘Cold Gin - Live’ (KISS, 1975), ‘Funkier Than a Mosquito’s Tweeter’ (Nina Simone, 1974), ‘Mosquito’ (Yeah Yeah Yeahs, 2013) and ‘Gin and Juice’ (The Gourds, 1998). Enjoy!

The Thought

Today’s quote is from Marcus Aurelius (he’s appeared before - I like him):6

“If it is not right do not do it; if it is not true do not say it.”

If you have a thought on this Thought - or any part of today’s issue - please leave a comment below:

And that’s the end of this stop - I hope you enjoyed a brief diversion from your regular journey!

Thanks to everyone who subscribes - I genuinely appreciate your interest and support. If you like The Bus, please SHARE it with a friend or several hundred.

If you haven’t climbed aboard, please do!

Until the next stop …

Only the female mosquito bites humans.

The gin and tonic originated in British colonial India, purportedly when medicinal quinine was mixed with gin and other other ingredients to make the bitterness more palatable. As British soldiers were provided with a regular gin ration the concoction was easy to make. For a good article about the invention of the gin and tonic – complete with a discussion about the proportion of quinine required to have any medical effect (let’s just say it’s a LOT more than you’d find in modern tonic water) see: Gin and Tonic (Country Life)

Quinine works by interfering with the growth and reproduction of the malarial parasites, which inhabit the red blood cells. This causes the parasites to disappear from the blood, dramatically improving an infected person’s condition. However, as quinine doesn’t kill the parasites in any other cells, once the treatment is stopped many patients will experience another malarial attack several weeks later as the parasites re-enter the bloodstream.

Winegard is Assistant Professor of History at Colorado Mesa University. For a brief biography and curriculum vitae, see: Winegard

Apologies to the bookstore (and it was a fantastic one: Munro's Books), but I didn’t have to wedge it into the already-bursting suitcase.

For a biography, see: Marcus Aurelius (Britannica)