Welcome aboard The Bus!

The Stop

Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822) was an English poet and one of the masters of the English Romantic movement. Equally passionate in his search for both ‘personal love and social justice,’ his work is considered among the greatest in the English language. The primary themes of English Romanticism - ‘restlessness and brooding, rebellion against authority, interchange with nature, the power of the visionary imagination and of poetry, the pursuit of ideal love, and the untamed spirit ever in search of freedom’ - were exemplified by Shelley in both the way he lived his life, and in the remarkable body of work he left behind after drowning off the coast of Italy at the age of 29.1

Born on 4 August 4 1792, Percy Bysshe Shelley2 was the elder son of Timothy and Elizabeth Shelley. In line to inherit his grandfather’s estate and baronetcy, as a child he was ‘beloved and admired’ by his family and ‘even the servants’ in the family home near Horsham, Sussex. As a young boy he revealed a prodigious imagination, devising games to play with his sisters and telling ghost stories to ‘an enrapt and willing-to-be-thrilled audience.’

When he was ten, Shelley was sent to Syon House Academy, where he experienced the ‘usual bullying, made all the worse by his failure to control his temper and his poor skills in fighting.’ At twelve he entered Eton, where - ‘slight of build, eccentric in manner, and unskilled in sports or fighting’ - he was ‘mercilessly baited by older and stronger boys.’ Nicknamed ‘Mad Shelley’ and ‘Shelley the atheist,’ he resisted physical and mental bullying by ‘indulging in imaginative escapism and literary pranks,’ interpreting the ‘petty tyranny’ of his teachers and schoolmates as ‘representative of man’s general inhumanity to man.’ Following Eton he entered University College, Oxford, but his career was cut short when he was expelled in March 1811 for publishing The Necessity of Atheism with his friend Thomas Jefferson Hogg.3

Moving to London, Shelley became interested in a ‘test of his zeal for social justice,’ which led him to meet 16-year-old Harriett Westbrook, the younger daughter of a well-to-do tavern keeper. A falling out with her father4 led her to seek Shelley’s ‘protection,’ and in August 1811 the 18-year-old Shelley eloped with Harriett to Edinburgh where they got married, against his belief that marriage was a ‘tyrannical and degrading social institution.’ Moving from place to place, financed by a small allowance ‘granted reluctantly’ by their families, they settled for a time in London where Shelley became a ‘disciple of the radical social philosopher William Godwin,’ and in 1813 he published his first important work, Queen Mab.5

In June 1813 Harriet gave birth to their daughter, Ianthe, but within a year Shelley had fallen in love with Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, daughter of William Godwin and his first wife, the women’s rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft. Against her father’s objections, the couple left England to travel through France, Switzerland, and Germany. When lack of funds forced them to return six weeks later to London, Shelley found the ‘general public, his family, and most of his friends regarded him not only as an atheist and revolutionary, but also as a gross immoralist.’ When Harriett - pregnant by an unknown lover - drowned herself in despair two years later, he was finally free to marry Mary Godwin6 and in 1818 they moved to Italy. Seeing himself in the role of an ‘alien and outcast, scorned and rejected by the human race to whose welfare he had dedicated his powers and his life,’ Shelley would never return to England.

It was in these circumstances - and with no established audience - that he would produce his greatest works. In 1819 he wrote his ‘masterpiece,’ Prometheus Unbound, and a tragedy, The Cenci. He would also produce numerous lyric poems, including ‘Ode to the West Wind’; a ‘visionary call for a proletarian revolution,’ The Mask of Anarchy; and a ‘penetrating political essay, A Philosophical View of Reform. Over the next two years, he wrote A Defence of Poetry,7 Epipsychidion - a ‘rhapsodic vision of love as a union, beyond earthly limits’ - and Adonais, a ‘noble elegy’ that commemorates the the death of the poet John Keats, but also contains an eerie prediction of his own death. In the last stanza, Shelley describes his spirit as a ‘ship driven by a violent storm out into the dark unknown.’ On 8 July 1822, he and a friend, Edward Williams, were sailing in the Gulf of Spezia, when a violent storm capsized their boat, killing both.

The Detour

Today’s Detour is to Sjaella’s ‘Northern Lights’ (4:01). Sjaella is a female vocal sextet from Leipzig, and this performance is a setting by the contemporary classical Norwegian composer Ola Gjeilo.8 It is an amazing piece of music, and worth the four minutes. And the next four minutes when you listen to it again.

The Recommendation

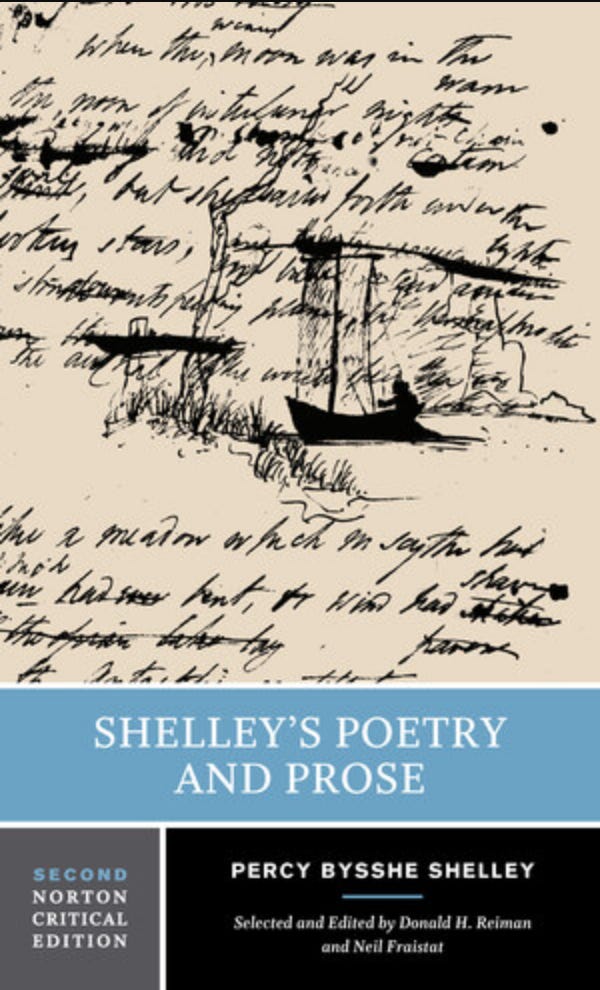

Today’s Recommendation is the Norton Critical Edition of Shelley’s Poetry and Prose (2002). An indispensable companion to the poet’s work, as is typical of the Norton versions the collection is exhaustive, updated with the latest scholarship, and filled with critical commentaries from the 19th century to the present. It’s a bit much if you’re just curious about him (in that case, check out his pages on poetryfoundation.org), but if you want more - and like your books physical - it’s a great place to start.

Remember: you can pick up Shelley’s Poetry and Prose at new and used independent bookstores, charity shops and - of course - the library.

The Sounds

Today’s playlist is a selection of five pieces from Romantic composers: ‘Liebesträume, S. 541: No. 3, Oh Lieb, so lang du lieben kannst ’ (Franz Liszt, 1850), ‘Rhapsody in G Minor, Op. 79, No. 2’ (Johannes Brahms, 1879), ‘Finlandia, Op. 26’ (Jean Sibelius, 1899), ‘Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-Flat Major, Op. 73 ‘Emperor’: II: Adagio un poco mosso’ (Ludwig van Beethoven, 1811) and ‘Ave Maria, D. 839’ (Franz Schubert, 1825). Enjoy!

The Thought

Today’s Thought is, of course, from Percy Shelley. It is from his short poem ‘To —’, written in 1821 but published two years after his death by Mary Shelley. I thought it particularly appropriate after today’s Detour:

‘Music, when soft voices die, vibrates in the memory.’

If you have a thought on this Thought - or any part of today’s issue - please leave a comment below:

And that’s the end of this Stop - I hope you enjoyed the diversion!

Thanks to everyone who subscribes - your interest and support is truly appreciated. If you like The Bus, please SHARE it with a friend or two.

If you haven’t climbed aboard The Bus, please do!

If you like The Bus, why not check out other newsletters?

The Sample sends out articles from blogs and newsletters across the web that match your interests. If you like one, you can subscribe with one click.

Until the next Stop …

I’ve been a fan of Shelley since I first read him in high school. He’s a complicated topic - more than a single Stop can cover - so I’ve done a very superficial sketch of his life and work. For more information, see the sources for today’s Stop: Shelley (Poetry Foundation), Shelley (Britannica) and Abrams, M. H. The Norton Anthology of English Literature, Vol. 2. London: WW Norton, 1986.

‘Bysshe’ was from his grandfather, a peer of the realm.

It didn’t help that they distributed copies to the conservative Oxford dons in an attempt to rile up the establishment. Hogg later became one of Shelley’s biographers.

Basically, he wanted her to go to boarding school and she did not. Shelley decided to rescue her from her father’s insistence she be formally educated.

This is a long prophetic poem in which the fairy Mab ‘reveals in visions the woeful past, the dreadful present, and the utopian future. Announcing that ‘there is no God!’’ the poem ‘decries institutional religion and codified morality as the roots of social evil,’ and ‘prophesies that, under the rule of the goddess Necessity, all insitutions will wither away, and humanity willl return to its natural condition of goodness and felicity.’

Who would, of course, now be Mary Shelley - best known as the author of Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818).

Shelley ‘eloquently declares that the poet creates humane values and imagines the forms that shape the social order: thus each mind recreates its own private universe, and ‘Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the World.’ Grand stuff, indeed.

For more information about Sjaella, see: Sjaella. For more information about Ola Gjeilo, see: Ola Gjeilo.

I'm a big fan of Shelley, along with Byron and Keats. My favorite? Depends on the day and the mood, but Ozymandias is one of my favorite poems.

Very enjoyable article about Shelley. I didn't know there was a Norton just on Shelley. I have a Norton anthology that includes him. The Norton books are excellent in terms of scholarship I think