Mummy

For art AND medicine? Who would have thought? (The Bus 6.10)

Welcome aboard The Bus!

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED (1.41) 25 AUGUST 2022

The Stop

Mummy (or mummy brown) was a popular pigment used by European painters from about the 16th century. Made from ground Egyptian mummies, the deep brown colour was prized for its ‘rich, transparent shade.’ Blended with a drying oil and amber varnish, mummy - also known as Egyptian brown and Caput mortum1- was used from the twelfth century until it finally went out of fashion in the mid-twentieth century.

For over 3,000 years, mummification was common in Egypt. In a complex process, the internal organs were removed before the body was embalmed with a mixture of spices, preservatives, beeswax, resins, asphalt and sawdust. Combined with a lengthy drying period, the process meant that mummified remains were very dark - which led to the mistaken belief they contained bitumen,2 a substance prized for its supposed medical applications. Believing mummies contained bitumen, from around the first century ground mummy - or ‘mummia’ - was ‘applied topically or mixed into drinks to swallow, and it seemed there was almost nothing it could not cure.’ It was also used as toothpaste, a topical salve for bruising, for the ‘staunching or blood’ and even to treat dysentery and epilepsy. From the Middle Ages until the 18th century, ‘mummy’ was a ‘standard product of apothecary shops,’3 and as these shops sold pigments, the ‘rich brown powder also found itself on painters’ palettes.’

By the mid-19th century, some artists were growing ‘dissatisfied with the pigment’s permanency and finish,’ along with becoming ‘more squeamish about its provenance.’ This reduction in popularity was probably a combination of its ‘grisly origins’ and the significant lack of available mummies due to the ‘increasing respect for [their] scientific, archaeological, anthropological and cultural importance.’ Whatever the actual reason, when the Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones was told one Sunday lunch by a friend about recently watching a mummy being ground into pigment, he ‘hastened to the studio, and returning with the only tube he had, insisted on … giving it a decent burial there and then.’4

By the early 20th century, the production of the pigment suffered from a lack of quality mummies.5 Until 1933 the London-based C Roberson and Co. - one of ‘Europe’s preeminent’ pigment producers (or ‘colourists') - continued to feature mummy in their catalogue, and though ‘mummy parts’ were reportedly seen in the shop as late as the 1980s, they officially ran out of supplies in the 1960s - much to the company’s dismay. In a 1964 interview with Time magazine, the managing director commented that while they might still have a ‘few odd limbs lying around somewhere,’ these weren’t ‘enough to make any more paint. We sold our last complete mummy some years ago for, I think, £3. Perhaps we shouldn’t have. We certainly can’t get any more.’

The Detour

Today’s Detour is to an article from Harvard Magazine about Milman Parry. A scholar of Greek who died at the age of 33, his obsession into the origin of the Odyssey and the Iliad led him to the wandering singers of Serbia - which convinced him the epics were produced by an oral, rather than written culture. A brief and interesting read with some great period photographs.

The Recommendation

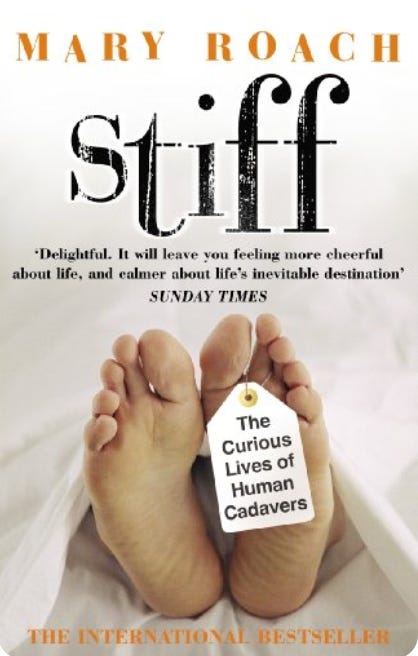

Today’s book is Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers, by Mary Roach (2003). In short, it’s everything you ever wanted (or didn’t want) to know about what happens to bodies after they die. From medieval pharmacies, artistic uses, body snatching, airplane accidents and forensic research Body Farms - this book explores the physical ‘afterlife’ in a fascinating and humorous way. I read it when it first came out and can still remember vividly some of the chapters. An excellent read. Highly recommended - if this sort of thing is of interest!

From the back: Fertilizer? Crash Test Dummy? Human Dumpling? Ballistics Practise? Life after death is not as simple as it looks. Mary Roach's Stiff lifts the lid off what happens to our bodies once we have died. Bold, original and with a delightful eye for detail, Roach tells us everything we wanted to know about this new frontier in medical science. Interweaving present-day explorations with a history of past attempts to study what it means to be human Stiff is a deliciously dark investigation for readers of popular science as well as fans of the macabre.

For a review in The Guardian: Meat and Mind

The Sounds

Today’s playlist is composed of songs that either seemed to fit today’s topic - or happened to fit together: ‘Bury Me’ (The Smashing Pumpkins, 1991), ‘Dirt’ (Alice in Chains, 1992), ‘Angel’ (Massive Attack, 1998), ‘Two Thousand and Seventeen’ (Four Tet, 2017) and ‘Rabbit In Your Headlights’ (UNKLE feat. Thom Yorke, 1998). Enjoy!

The Thought

Today’s Thought is a quotation from the Greek Stoic philosopher Epictetus:6

‘Keep silent for the most part, and speak only when you must, and then briefly.’

If you have a thought on this Thought - or any part of today’s issue - please leave a comment below:

And that’s the end of this stop - I hope you enjoyed a brief diversion from your regular journey!

Thanks to everyone who subscribes - I genuinely appreciate your interest and support. If you like The Bus, please SHARE it with a friend or several hundred.

If you haven’t climbed aboard, please do!

Until the next stop …

Or … ‘dead man’s head’.

Bitumen is a dense, highly viscous petroleum-based hydrocarbon - a world away from mummies. However, the Persian word for bitumen was mumiya - leading to the belief that mummies contained the chemical.

When the demand for Egyptian mummies began to outrun their supply, some dealers addressed the shortage by treating the bodies of recently ‘executed criminals or slaves,’ with bitumen and ‘exposing them to the sun, to produce mummified tissue which was then sold as authentic.’

The event was recounted decades later by Burne-Jones’s nephew Rudyard Kipling, who’d been a teenager at this Sunday lunch: ‘He [Burne-Jones] descended in broad daylight with a tube of ‘Mummy Brown’ in his hand, saying that he had discovered it was made of dead Pharaohs and we must bury it accordingly. So we all went out and helped … and to this day I could drive a spade within a foot of where that tube lies.

A 1904 ad in the Daily Mail asked for an Egyptian mummy ‘at a suitable price’ to ‘be used for adorning a noble fresco in Westminster Hall.’

The quote - which is certainly Stoic in theme but could arguably be Buddhist - is attributed to Epictetus, though there is no definite source available. Nevertheless, he’s quite an interesting character and a formidable thinker from the 1st/2nd centuries. For a very thorough survey of his life and thought, see: Epictetus (Stanford).

Who knew? Turns out we can all see dead people!