Machiavelli

Defining politics since 1513. (Vol. 2; Issue 43)

Welcome aboard The Bus!

The Stop

Niccolò Machiavelli (1469-1527) was an Italian Renaissance diplomat, political philosopher and secretary of the Florentine Republic. Despite coming from a ‘wealthy and prominent’ family, his father - a doctor of laws - was one of its poorest members and became an ‘insolvent debtor’ who was barred from public office. Nevertheless, he owned a small property near Florence1 and had a library from which his son added to the ‘typical humanist education’ expected of his social status. This education served him well, for Machiavelli progressed quickly through the Florentine government and for many years was in charge of the Republics’s foreign affairs - a position which sent him on over 40 diplomatic missions throughout the Italian city-states. These experiences - through which he saw first-hand the corruption, deceit and treachery displayed by entities as varied as the Holy Roman Empire, the Papacy, the Borgias and the Medici - gave him insight into the true nature of politics and led to his most famous book, The Prince.2

Written in 1513, but not published until 1532 (five years after his death), The Prince is a short treatise nominally concerned with instructing future princes on how to ‘acquire power, create a state, and keep it.’ Prior to Machiavelli, works of this sort advised rulers to become their best by following virtuous role models, but Machiavelli recommended a prince forgo the standard of “what should be done” and go directly to the “‘effectual truth” of things. Rather than emulating or embodying a moral standard or virtue, Machiavelli’s prince was to be ‘guided by necessity’ rather than vague idealism. By basing his instructions on responding to reality, Machiavelli became the founder of modern political science – a ‘discipline based on the actual state of the world as opposed to how the world might be in utopias’ such as those found in Plato’s Republic or St Augustine’s City of God.3

Machiavelli believed humans are ‘wretched creatures, governed only by the law of their own self-interest.’ A prince who doesn’t realise this is doomed to fail, for while people are content, happy and trustworthy in prosperous times, they will turn selfish and deceitful - and revolt against him - when things go wrong. Similarly, a prince who is concerned with being liked - with being loved - is doomed to fail, because ‘love is fickle’ and can change on a whim. Consequently, Machiavelli teaches that it is ‘better for a prince to be feared than loved, because … fear is constant.’ Virtues such as honour, generosity and courage - previously the standards rulers were expected to uphold - are reinterpreted from the aspect of their usefulness. In Machiavelli’s hands, every virtue - and its corresponding vice – becomes a means to an end because every action a prince takes must be made with respect to its effect on the state – never in terms of any intrinsic moral value. In fact, for Machiavelli there is ‘no moral basis on which to judge the difference between legitimate and illegitimate uses of power.’ Power and authority are ‘coequal: whoever has power has the right to command’ and a ‘good person has no more authority by virtue of being good.’

Machiavelli defined politics by the difference separating the ‘ancients and the moderns:’4 the pagan ancients were strong, while the moderns - ‘formed by Christianity’ - were weak. For Machiavelli, the only ‘real concern of the political ruler is the acquisition and maintenance of power,’ and in the Discourses on Livy5 he blamed the Roman Catholic Church – and Christianity itself – for the ‘cause of Italy’s disunity.’ He accused the clergy of dishonesty, chastised them for teaching people ‘that it is evil to say evil of evil,’ and condemned Christian teachings for ‘[glorifying] suffering and [making] the world effeminate.’ It is unclear whether he preferred atheism, paganism or a reformed version of Christianity,6 but his attacks on the Church in combination with his version of morality meant his works were placed on the Church’s Index Librorum Prohibitorum (‘Index of Forbidden Books’) when it was made in 1564. Nevertheless, Machiavelli continued to be read, and his distinctively original thought - both ‘troubling yet stimulating’ - has cemented his place in Western political philosophy.

The Detour

Today’s Detour is to Grand Canons d’Alain Biet (10:44). Biet’s drawings of innumerable everyday objects are combined in a whirlwind of stop action animation - and the result is unbelievable. This is one of my favourite Detours yet - please give it a look.

The Recommendation

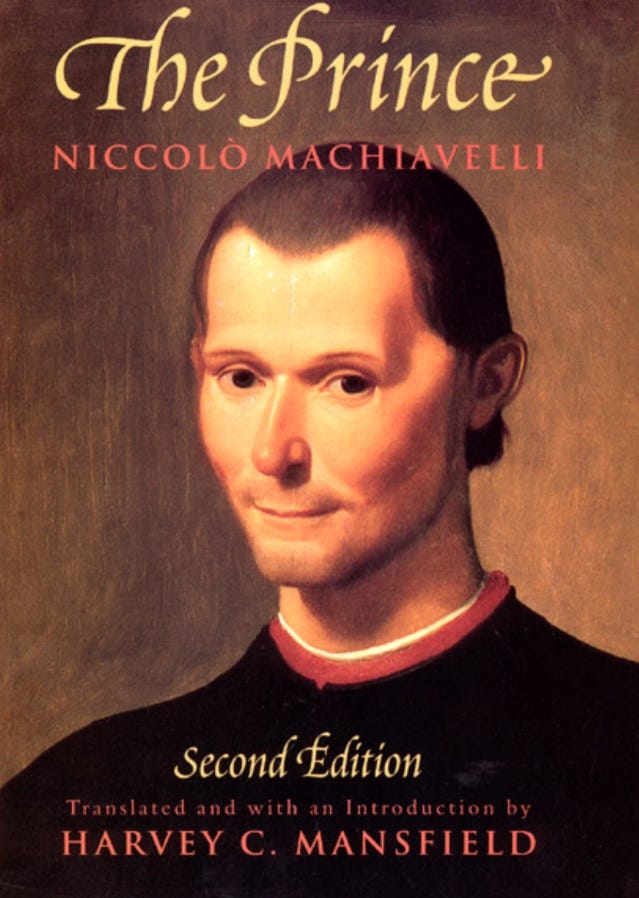

Today’s recommendation is Machiavelli’s The Prince (1513). Based upon his experiences as a Florentine diplomat and steeped in his understanding of history, The Prince is a ‘short treatise on how to acquire power, create a state, and keep it.’ Controversial from its first publication, it’s essential reading for anyone interested in human nature and politics.7

You can buy The Prince from Amazon, but you can also get it from your local new or used bookstore - or check it out from the library. And those options are better for everyone.

The Sounds

Today’s playlist is composed of five tracks that have been sitting in my ever-growing ‘To Use’ folder which seemed to work as a soundtrack while writing this issue of The Bus: ‘Apocalypse’ (Cigarettes After Sex, 2017), ‘Love 2 Fast’ (Steve Lacy, 2019), ‘Palaces of Montezuma’ (Grinderman, 2010), ‘Paper Tiger’ (Beck, 2002) and ‘Fake Empire’ (The National, 2007).8 Enjoy!

The Thought

Today’s Thought is from Machiavelli’s The Prince. This advice to a would-be ruler has become part and parcel of modern politics, but I’d argue it’s a fundamental reality of all human interaction:

‘Everyone sees what you appear to be, few experience what you really are.’

If you have a thought on this Thought - or any part of today’s issue - please leave a comment below:

And that’s the end of this Stop - I hope you enjoyed the diversion!

Thanks to everyone who subscribes - your interest and support is truly appreciated. If you like The Bus, please SHARE it with a friend or two.

If you haven’t climbed aboard The Bus, please do!

If you like The Bus, why not check out other newsletters? Each morning, The Sample sends out articles from random blogs and newsletters from across the web that match your interests. If you like one, you can subscribe with one click. I’ve signed up to several and highly recommend it.

Until the next Stop …

He supplemented the meagre income he received from it with ‘earnings from the restricted and almost clandestine exercise of his profession.’

Machiavelli is a very complicated subject far beyond the scope of a single Bus Stop. Consequently, I’ve chosen to look briefly at the general themes in his thought at the expense of his biography. He’s fascinating - and I’d encourage you to look deeper into him. Sources for today’s Stop include: Machiavelli (Britannica), The Prince (Britannica), What Can You Learn from Machiavelli? (Yale), Machiavelli (Stanford) and The Discourses on Livy (Britannica).

Containing quotes such as ‘if an injury has to be done to a man it should be so severe that his vengeance need not be feared,’ and ‘never attempt to win by force what can be won by deception,’ The Prince led to Machiavelli’s identification as a proponent of amorality and as such his name has become an adjective meaning ‘cunning, scheming, and unscrupulous, especially in politics.’

In a nutshell, the ‘ancients’ were the rulers of the Roman Republic; the ‘moderns’ were the rulers of the various splintered principalities and city-states dotting the Italian landscape and loosely connected under the umbrella of the Roman Catholic Church.

Machiavelli wrote numerous books, treatises and poems, and though The Prince is his most famous, the Discourses on Livy (1531) is a founding document on modern republicanism that is as important - and controversial - as The Prince. For more information, see the the link in Footnote 2.

In a letter dated 16 April 1527 (two months before his death), he wrote: ‘I love my fatherland more than my soul.’

I first read this in an undergraduate political science course on Modern Political Theory and was struck by his tone: frank, to the point and brutal. I’ve since read it a couple of times and explored the impact of Machiavelli’s repurposing of virtue into virtú in some grad school work. It’s my favourite work from the Italian Renaissance - and I’d argue it’d be hard to find one that’s had a greater impact in politics, economics and society in general. And that’s not necessarily a good thing.

I originally selected five tracks contemporary to Machiavelli - but changed my mind: you’ve got to be in a certain mood to hang out with late 15th/early 16th century Italian music and at the moment I’m not. On another note, when looking at the dates of these tracks I hope I’m not the only one shocked that the Beck one is 21 years old. Tempus fugit and all that, but 21 years?!

Alain Biet is one prolific artist and extremely talented watercolorist! Wow. Nice detour after the dark path I went down thinking about how many present day US politicians must regard Machiavelli's Prince as gospel.