Welcome aboard The Bus!

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED (2.1) 3 OCTOBER 2022

The Stop

In philosophy, a category mistake occurs when two logically different things - objects, ideas, etc. - are erroneously believed to possess fundamentally similar values. Though category mistakes have been the subject of philosophical inquiries since at least as early as Aristotle, the term gained widespread use in the mid-20th century when the English philosopher Gilbert Ryle (1900 - 1976) used it to ‘explode the myth’ of Cartesian dualism’s concept of the mind and body as two ontologically distinct substances that nevertheless somehow interact.1

First expressed by the French mathematician, scientist and philosopher René Descartes (1596 - 1650)2 in Meditation 6,3 substance dualism was for centuries the dominant philosophical explanation for the relationship between the mind and body. Believed to be completely distinct substances, the two were necessarily very different. For example, Descartes argued that - unlike the body - the mind neither exists in space nor has any parts. Though not all philosophers contemporary to Descartes or after him agreed,4 his theory remained the official explanation in large part because it allowed for the ‘hope of another life after death.’ Descartes’s separation of mind and body into two substances allowed for the belief that - though connected in life5 - while at death ‘the body dies and decomposes, this will not extinguish the mind.’

Ryle thought this ‘official doctrine’ of the relationship between mind and body was fundamentally flawed as it was built upon a category mistake. To explain his objection, Ryle compared the Cartesian or dualist philosopher who ‘wonders what kind of thing the mind could be and how it interacts with the body’ to a foreigner in England who watches a cricket match for the first time.6 The visitor is taught which team members are responsible for the batting, bowling, wicket-keeping and fielding and the various tasks for each role are explained. But half-way through the game the foreigner asks, ‘I’ve heard a lot about the importance of team spirit. Who is responsible for that?’ And this confusion - taking the term ‘team spirit’ to designate something similar to, but distinct from, the other cricketing tasks - ‘reflects a category mistake.’ Rather than understanding that the expression ‘team spirit’ refers to how well the team plays together, the visitor mistakenly treats a concept from one logical category (team spirit) as belonging to a different logical category (cricketing tasks).

Analogously, Ryle believed Descartes’s fundamental mistake was to think of the mind as an entity - some kind of thing that belonged in the same logical category as that of the physical body. Yet when bodies and brains are examined, no ‘mentality’ of any sort is found. Consequently, if ‘minds are entities … they must be entities of a special sort, nonmaterial entities.’ But for Ryle, this claim itself is a mistake: Descartes and his followers are wrong because ‘mind’ is not an entity or thing - in fact, it is ‘not a substance at all.’ Rather, Ryle argued that when we use the term ‘mind’ we are actually speaking about a collection of behaviours. Instead of a separate substance that somehow inhabits the body like a ‘ghost in the machine,’ the term ‘mind’ is actually just our ‘way of talking about the capacities of human beings to perform a whole range of actions.’ For Ryle, the distinction between ‘talk about minds and … talk about bodies … is not talk about two different substances,’ purely because ‘mental concepts are not of the same category as those of material bodies’ - and to think otherwise is ontologically wrong.

The Detour

Today’s Detour is to a short (13:50 minutes) TEDx lecture by Dr Cal Newport, computer scientist. He has never had a social media account and wants more people to reduce - or even eliminate - their use of social media as it isn’t a ‘fundamental technology,’ but actually just another form of entertainment with rather harmful effects. It’s thought-provoking and research-backed throughout. Let me know your thoughts!

The Recommendation

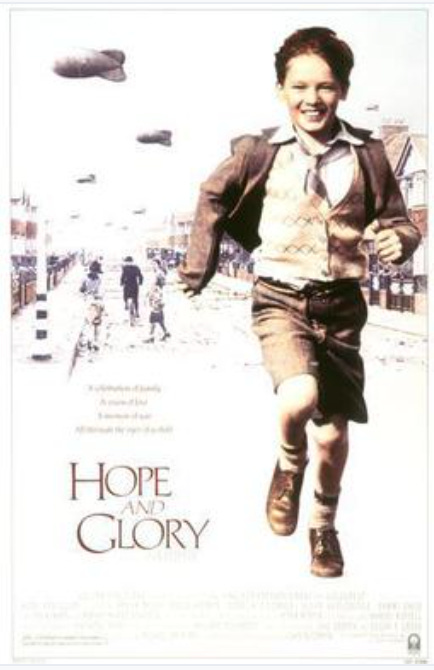

Today’s Recommendation is a film - John Boorman’s Hope and Glory (1987). Drawn from Boorman’s own childhood experience growing up in London during World War II, Hope and Glory is the story of the war as seen through the eyes of ten-year-old Billy Rowan, juxtaposing the ‘magic of childhood amongst the chaos of war.’ A comedy/drama, the film was very successful upon its release - especially in Britain - and won numerous awards, including the Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture - Musical or Comedy, 13 BAFTA Award nominations, and five Academy Award nominations including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Original Screenplay.

Trailer: Hope and Glory (1987 Trailer)

Review: Hope and Glory (Roger Ebert, 1987)

The Sounds

Today’s playlist is a collection of tracks I’ve recently been listening to and (with exception of the title of the album from which The Police one is taken) has no connection to the Stop: ‘Darkness’ (The Police, 1981), ‘Gold Dust Woman’ (Julia Holter, 2012), ‘High School Gym’ (Dougie Poole, 2022), ‘Only’ (RYX, 2016) and ‘Forest Dark’ (Nailah Hunter, 2022). Enjoy.

The Thought

Today’s Thought is from the 19th century American novelist, journalist and humourist, Mark Twain:7

‘The man who does not read has no advantage over the man who cannot read.’

If you have a thought on this Thought - or any part of today’s issue - please leave a comment below:

And that’s the end of this stop - I hope you enjoyed the diversion!

Thanks to everyone who subscribes - your interest and support is truly appreciated. If you like The Bus, please SHARE it with a friend or two … or several hundred.

If you haven’t climbed aboard The Bus, please do!

Until the next stop …

A few definitions. In this context, ‘substance’ refers to a basic ‘kind of stuff or thing’ which depends on nothing else for its existence. (Conversely, a ‘property’ is something that does depend on something else for its existence - namely, a substance. For example, if ‘water’ is a substance, its property is ‘wetness.’) The claim the mind and body are ontologically distinct substances means that on an ‘ontological’ level - i.e., the most basic, fundamental level of their existence - neither requires anything else - including the other - to exist. Thus, for Cartesian dualists, both the mind and body exist entirely independently from each other - while at the same time interacting as a well-tuned machine. Yes, this is a complicated topic - and difficult to cover adequately in the confines of a Stop. However, if you’re interested in more information about category mistakes - or philosophy of mind in general - you should check out today’s sources: Category Mistakes (Stanford); Cardinal, Daniel, Gerald Jones and Jeremy Hayward. AQA A2 Philosophy. London: Hodder, 2015; Cardinal, Daniel, Gerald Jones and Jeremy Hayward. Philosophy For A-level Year 2: Metaphysics of God and Metaphysics of Mind. London: Hodder, 2018; and Heil, John. Philosophy of Mind: A Contemporary Introduction. 3rd Ed. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Thus why it’s called ‘Cartesian.’ For more information about Descartes, see: Descartes (Britannica).

The Meditations (full title: Meditations on First Philosophy, in Which is Proved the Existence of God and the Immortality of the Soul) (1641) is his magnum opus and one of the most influential works in the history of philosophy. For more information, see: Descartes - Meditations (Britannica).

And there were many, not least of which was the amateur philosopher Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia. A former student of Descartes, Princess Elisabeth maintained a vigorous correspondence with him and was not shy about querying parts of his claims with which she disagreed. In particular, she questioned how the mind - which doesn’t exist in physical space - has the ability to make changes in physical space: how, for example, can this non-material substance cause my physical hand to move? For more information about Princess Elisabeth, see: Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia (Stanford).

Exactly how this worked was something Descartes had yet to establish at his death, though he was leaning towards a connection in the brain at the point of the pineal gland - the purpose of which at the time was still unknown.

I genuinely feel for this foreigner. I’ve lived in England for over 20 years and though many friends have attempted to explain the game, it's only been in the last few years since my son started playing that it’s actually begun to make sense. Nevertheless, though I’d be hard pressed to explain it beyond a few basic points, I really enjoy watching cricket - there’s really nothing quite like it.

For more information, see: Mark Twain (Britannica).