Agnosticism

A logical approach to an illogical question. (The Bus 3.32)

Welcome aboard The Bus!

The Stop

Agnosticism (from Greek agnōstos, ‘unknowable’) is the doctrine that ‘humans cannot know of the existence of anything beyond the phenomena of their experience.’ First coined publicly in 1869 by biologist and ‘champion of the Darwinian theory of evolution’ T. H. Huxley at a meeting of the Metaphysical Society in London,1 the original term was not intended to exclusively equate with a religious stance. However, from the beginning agnosticism has become understood popularly as referring to ‘scepticism about religious questions in general,’ along with the ‘rejection of traditional Christian beliefs under the impact of modern scientific thought.’

Huxley initially used agnostic to describe his personal position with regard to religion: ‘It came into my head as suggestively antithetical to the ‘Gnostic’ of Church history who professed to know so much about the very things of which I was ignorant.’ Huxley’s statement hints at the dual nature of the term, namely that agnosticism refers to (1) the need to accept ‘not knowing,’ but in particular (2) in a ‘not knowing’ that ‘refers … to the sphere of religious doctrine.’ However, rather than a ‘profession of total ignorance … even of total ignorance within one special but very large sphere,’ Huxley insisted agnosticism was ‘not a creed but a method.’ Rather than merely enabling someone to justify an inability to make a clear decision by claiming a lack of evidence, Huxley’s agnosticism was a scientific approach that would follow reason ‘as far as it can take you,’ before you ‘frankly and honestly … recognise the limits of your knowledge.’

Though agnostic elements can be tenuously found in ancient Greek philosophy,2 Huxley’s most ‘important and immediate source of … agnostic ideas was surely David Hume.’3 Huxley’s insistence that a thinker ‘recognise and limits of his knowledge’ is rooted in Hume’s ‘attempts … to determine the limits of man’s possible knowledge.’4 Following this logic, therefore, agnostics are individuals who have studiously reached the limits of their possible knowledge and decide that the question of God’s existence cannot be answered definitively because either (1) there is no evidence to support either side of the argument, or (2) because the concept of God is beyond human understanding.5

The Detour

Today’s Detour is ‘Why is North up?’ a short (9:56) exploration of why North is at the top of maps - and seems to have always been so. It’s an interesting video (there are two ads at the beginning, but you can skip the second one soon after it starts) that effectively challenges - and changes - perspective. It’s certainly worth a watch!

The Recommendation

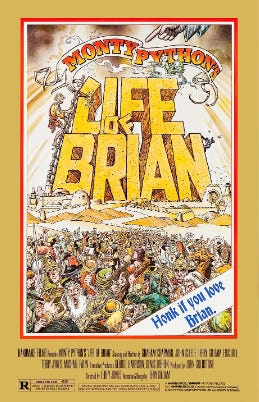

Today’s Recommendation is Monty Python’s The Life of Brian (1979). Directed by Terry Jones and written by and starring the Monty Python comedy group (Jones, Graham Chapman, John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Eric Idle and Michael Palin), the film tells the story of Brian Cohen, a hapless everyman who just happened to be born on the same day right next door to Jesus - and is mistakenly identified as the Messiah. Released to critical and commercial success, the film’s religious satire was not welcome in many quarters and subsequent years saw the movie censored or even banned in various places world-wide. This reaction, of course, only served to help cement its place as a classic - not to mention that it’s very, very funny. Highly recommended.

The Life of Brian (1979) Trailer

The Sounds

Today’s playlist is composed of agnostic-friendly tracks - all of which are brilliant: ‘Gloria: In Excelsis Deo’ (Patti Smith, 1975), ‘God’ (John Lennon, 1970), ‘Into My Arms’ (Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds, 1997), ‘It Ain’t Necessarily So’ (Aretha Franklin, 1980) and ‘Losing My Religion’ (R.E.M., 1991). Enjoy!

The Thought

Today’s Thought is the opening and closing line from the Patti Smith song on today’s playlist:

‘Jesus died for someone’s sins, but not mine.’6

If you have a thought on this Thought - or any part of today’s issue - please leave a comment below:

And that’s the end of this Stop - I hope you enjoyed the diversion!

Thanks to everyone who subscribes - your interest and support is truly appreciated. If you like The Bus, please SHARE it with a friend or two.

If you haven’t climbed aboard The Bus, please do!

If you like The Bus, why not check out other newsletters?

The Sample sends out articles from blogs and newsletters across the web that match your interests. If you like one, you can subscribe with one click.

Refind picks five links from around the web that make you smarter, tailored to your interests. Refind is a must-read newsletter loved by over 200,000 curious minds. There’s also a very cool app. Sign up for free!

Until the next Stop …

Running from 1869-1880, the Metaphysical Society of London was a preeminent British debating society. Members - invitation-only and exclusively male - included prominent politicians, philosophers, scientists and members of the clergy. Huxley - grandfather of the British author Aldous Huxley (see The Bus 2.2, ‘Aldous Huxley’ (paywalled) - is quite an interesting character. For more information, see: TH Huxley (Britannica). Sources for today’s Stop include Agnosticism (Britannica).

‘Modern secular and atheist’ agnosticism can be traced back to the 5th century BCE, when the Oracle of Delphi recognised publicly Socrates as the ‘wisest of men’ precisely because he ‘knew what, and how much, he did not know.’ For more about the Oracle, see The Bus 3.28, ‘The Pythia’.

David Hume (1711-1776) was a Scottish philosopher, historian and economist known for his philosophical empiricism and scepticism. Hume is one of the most important thinkers of the late Enlightenment and his influences can be found everywhere. For more information, see Hume (Britannica).

In particular, this approach is found in Hume’s Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1748), which follows Locke and later Kant in an attempt to ‘determine the limits of man’s possible knowledge’, and in his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779).

There are two types of agnosticism: weak and strong. Weak agnosticism maintains the existence of God is either unknown or unknowable and therefore it is impossible to know God’s existence for certain. Strong agnosticism, however, is the belief that the existence of God is meaningless or irrelevant and therefore the very question of God’s existence is ‘not a meaningful one’.

Arguably, there are few album openers that set out the artist’s agenda as clearly. Brilliant.

I have been an evangelical agnostic for decades now.

Thanks, Bryan, for this topic.

Also, had not heard “Dear god” by XTC in ages and it came on while reading this article!

Excellent primer on what is arguably the most important 'position' any thinking person could suggest to oneself in our days of global conflict, wherein we tend to imagine we know more about the others than we do, or can, and even this to the point of stating that another does not know themselves; e.g. parents who object to their children's gender identities. Though I have personal symbolic realm beliefs, I have been a professional agnostic since age 12. It is the only sensible space for either a scientist or a philosopher, but more importantly, for anyone tempted - the term is used advisedly - to cast a judgment upon someone else a priori as it were.

But speaking 'About the Others', Substack has been pestering me to shill books, so I am going to take the liberty of using your comment space to do just that: https://www.amazon.com/About-Others-G-V-Loewen/dp/1682358836/ref=sr_1_1crid=10SN3I7ITHYZC&keywords=Loewen%2C+G.V.+About+the+Others&qid=1682816632&s=books&sprefix=loewen%2C+g.v.+about+the+others%2Cstripbooks-intl-ship%2C143&sr=1-1

'Paul Andrews is a man who isn't careful what he wishes for. The results are a spouse whose loyalty has been worn to a thread, an adoptive daughter who adores him too much, a therapist who looks the other way while he cheats with his wife, and friends who will do anything for him, including all the wrong things. Experiencing disturbing hallucinations and dreams, Paul is about to lead all of them and others straight into an existential abyss. The radically new knowledge of the human condition that is the result of this, may have been better off never having been known in the first place.'

A thoroughly dislikable novel with nary a sympathetic character; sounds much like our world story at the moment. Cheers, Greg