Welcome aboard The Bus!

The Stop

Released in the US on 19 December 1971 and in the United Kingdom on 13 January 1972, A Clockwork Orange is Stanley Kubrick’s ninth film, coming between the magisterial 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Barry Lyndon (1975). A dystopian science fiction/crime film based on the eponymous novel by Anthony Burgess, A Clockwork Orange ‘employs disturbing, violent images to comment on psychiatry, juvenile delinquency, youth gangs, and other social, political, and economic subjects in a … near-future Britain.’ Controversial from its release, A Clockwork Orange is a film that has become not only a cult classic but part of the ‘pop-culture firmament’.1

Described as an ‘artful dark comedy of violence’, A Clockwork Orange is considered by most critics to be the ‘most repellent film’ of Kubrick’s career.2 Kubrick’s thematic concerns about power and the morally bankrupt people who are corrupted by it - from the ‘decadent Romans of Spartacus to the careerist French military brass in Paths of Glory to deranged stewards of our nuclear arsenal in Dr Strangelove’ - now find expression in the story of a violent misfit who runs up against a British ‘society lost to authoritarian rule, where an experimental campaign to curb criminal behaviour leads to a deplorable form of social engineering.’

Synopsis:

In a futuristic Britain, 15-year-old Alex DeLarge leads a gang of ‘droogs’ who one night, after getting intoxicated on drug-laden ‘milk-plus’, embark on an evening of ‘ultra-violence’. Invading an unsuspecting writer’s home, they end up beating the writer to the point of crippling him and violently raping his wife while singing ‘Singing in the Rain’. The next day, while truant from school, Alex’s probation officer - who is fully aware of his activities - approaches and cautions him.

The droogs aren’t happy with petty crime, desiring better targets and higher-yield thefts - but Alex asserts his authority by attacking them and beating them into submission. However, during another home invasion - this time of a wealthy ‘cat lady’ who Alex proceeds to bludgeon with a phallic sculpture - the droogs turn on him and Alex is arrested. He later learns the woman has died of her injuries and he is sentenced to 14 years in prison for her murder.

Two years into his sentence, Alex is offered the opportunity to be a test subject for the Minister of the Interior’s new ‘Ludovico Technique’ - an experimental aversion therapy which claims to rehabilitate criminals in two weeks. As part of his treatment, Alex is strapped to a chair, his eyes are clamped open and he is injected with drugs while being forced to watch films of sex and violence, some of which are accompanied by the music of Beethoven - his favourite composer. As the association between the violent scenes and Beethoven becomes stronger, Alex becomes traumatised and nauseated by the films and, afraid the Ludovico Technique will make him sick when hearing Beethoven, begs for the treatment to end.

Ignoring his pleas, after two weeks of treatment, the Minister of the Interior demonstrates Alex's rehabilitation to a group of officials by showing he is unable to fight back against an actor who taunts and attacks him and that he becomes ill at the thought of having sex with a topless woman. While the prison chaplain worries that Alex has lost his free will, the Minister dismisses the loss as a small price to pay for a technique that will cut crime and reduce overcrowded prisons.

Released from prison, Alex discovers his possessions have been sold to raise compensation for his victims and his parents have rented his room. Encountering an elderly vagrant he had attacked years before, when the vagrant and his friends attack him, Alex is saved by two policemen who turn out to be his former droogs. They drive him to the countryside, beat him and nearly drown him before abandoning him. Alex barely makes it to the doorstep of a nearby home before collapsing.

Alex wakes to find he is in the writer’s home from the first evening of ultra-violence. Though the writer doesn’t remember Alex from the earlier attack, he knows of the Ludovico Technique from the newspapers. Seeing Alex as a potential political weapon, he decides to introduce him to his colleagues, but when he overhears Alex singing ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ he realises who he is. With help from his colleagues, the writer drugs Alex and locks him in an upstairs bedroom, playing Beethoven's Ninth Symphony loudly from the floor below. Unable to withstand the pain the music elicits, Alex tries to kill himself by jumping out of the window.

Alex survives the suicide attempt and wakes up in a hospital with multiple injuries and discovers the Ludovico Technique has failed and he no longer has aversions to violence and sex. The Minister of the Interior arrives and apologises, offering to take care of Alex and provide him with a job in return for help with his election campaign. As a sign of his goodwill, he presents Alex with a stereo system playing Beethoven's Ninth. Alex begins contemplating violence and has vivid thoughts about having sex with a woman in front of an approving crowd. The film ends with him thinking to himself, ‘I was cured, all right!’

But don’t take my word for it, check out the trailer: A Clockwork Orange (1972) Trailer.

The Detour

Today’s Detour is to 49 Mile Scenic Drive, a short (9:59) documentary about the iconic tourist drive through the city of San Francisco, the designer of its iconic signs and - well, what happens when an original piece of art gets slowly replaced by an inferior imitation. It’s a bizarre little film, but worth the time - even if you haven’t had the pleasure of driving this most interesting route.

The Recommendation

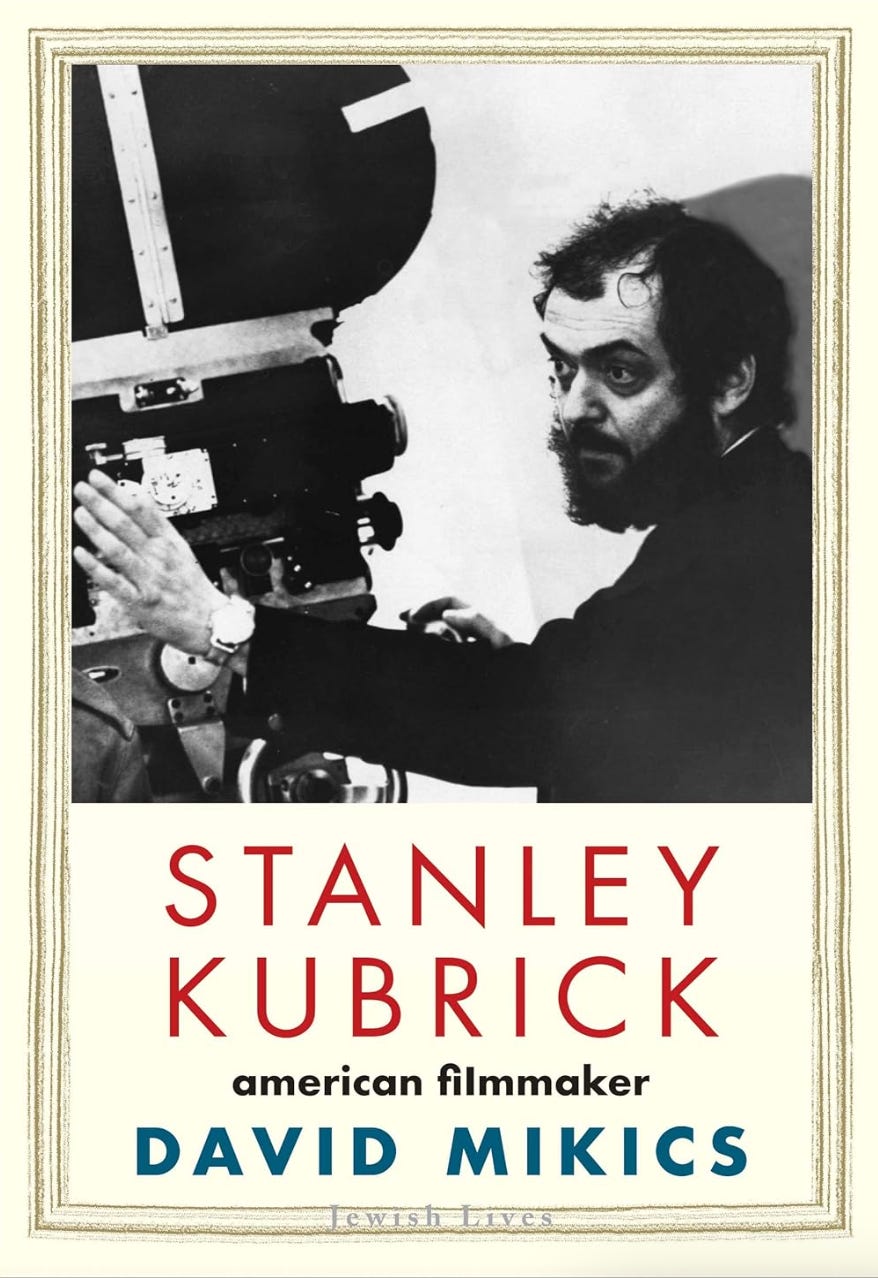

Today’s Recommendation is David Mikics’s Stanley Kubrick: American Filmmaker (2020).3 Part of the Jewish Lives series, this short biography and study of Kubrick is a great introduction to this most influential filmmaker. It’s a quick read, and absolutely worth the time if you’re interested in Kubrick.

From the back: Kubrick grew up in the Bronx, a doctor’s son. From a young age he was consumed by photography, chess, and, above all else, movies. He was a self‑taught filmmaker and self‑proclaimed outsider, and his films exist in a unique world of their own outside the Hollywood mainstream. Kubrick’s Jewishness played a crucial role in his idea of himself as an outsider. Obsessed with rebellion against authority, war, and male violence, Kubrick was himself a calm, coolly masterful creator and a talkative, ever‑curious polymath immersed in friends and family.

Drawing on interviews and new archival material, David Mikics for the first time explores the personal side of Kubrick’s films.

The Sounds

Today’s playlist is a selection of five tracks inspired by or otherwise connected to A Clockwork Orange: ‘Looking Down the Barrel of a Gun’ (Beastie Boys, 1989), ‘Ultraviolence’ (New Order, 1983), ‘Girl Loves Me’ (David Bowie, 2016), ‘Alex Descends into Hell for a Bottle of Mile/Korova 1)’ (U2, 1991) and ‘Temptation’ (Heaven 17, 1983). Enjoy!4

The Thought

Today’s Thought is from Stanley Kubrick:

‘If it can be written, or thought, it can be filmed.’

If you have a thought on this Thought - or any part of today’s issue - please leave a comment below:

And that’s the end of this Stop - I hope you enjoyed the diversion!

Thanks to everyone who subscribes - your interest and support is truly appreciated. If you like The Bus, please SHARE it with a friend or two.

If you haven’t climbed aboard The Bus, please do!

If you like The Bus, why not check out other newsletters?

The Sample sends out articles from blogs and newsletters across the web that match your interests. If you like one, you can subscribe with one click.

Until the next Stop …

Most of the controversy about the film stemmed from its (especially for the time) scenes of graphic sex and violence. In addition, several copycat crimes were blamed on its inspiration and the resultant furore caused Kubrick to withdraw it from distribution in the UK for 27 years. Which, of course, only made it more interesting. It’s a good film - but it is a challenging watch. Sources for today’s Stop include A Clockwork Orange (kubrick.fandom), A Clockwork Orange (Wikipedia), A Clockwork Orange (Britannica) and A Clockwork Orange at 50 (Guardian). For a decent list of the myriad of pop-culture references from The Simpsons, South Park, music and sports see: A Clockwork Orange List of Cultural References (Wikipedia).

Kubrick was never shy about challenging his audience. His other films include: Fear and Desire (1953), Killer’s Kiss (1955), The Killing (1956), Paths of Glory (1957), Spartacus (1960), Lolita (1962), Dr Strangelove (1964), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), Barry Lyndon (1975), The Shining (1980), Full Metal Jacket (1987) and Eyes Wide Shut (1999).

Mikics is a Moores Distinguished Professor in the English Department and Honors College at the University of Houston.

OK … the Beastie Boys track contains explicit references to both ultra-violence and A Clockwork Orange (lyrics I’ve heard over and over but only just clocked the reference, despite being a huge fan of Paul’s Boutique since its release) and New Order not only named this track after Alex’s interest in ultra-violence, but the band also took a lot of its aesthetic from the Kubrick film. ‘Girl Loves Me’ contains lyrics written in Nasdat - the language Burgess invented for his novel - and other Bowie songs, including ‘Suffragette City’, contain similar lyrical jaunts. The U2 track was recorded as part of the Achtung Baby sessions for The Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of A Clockwork Orange and released as a B-side to ‘The Fly’ in 1991. This was, of course, back when U2 were still mostly cool and Bono’s head hadn’t slipped up his own backside. And Heaven 17 took their name from a fictional band in Burgess’s novel. Interestingly, the fictional band had a hit that went to number 4 … ‘Temptation’ went to number 2.

Certainly every artist in differing genres alters the expression of the narrative whilst keeping some of its DNA intact, as is said. It is the mark of greatness, and Bach is himself the greatest exemplar to this regard, since he represents the summa of a millennium of Western music which until Monteverdi, was scattered in differing, even opposing, genres. Bach upshifted the whole thing and gave history an entirely new art form. All that said, see what you think of this piece:

https://gvloewen.ca/2022/07/22/bathing-with-bach-showering-with-shostakovich/

If only the soundtrack was on the streaming platforms...